The well-worn image of the traumatised comedian – the sad clown whose painted-on smile masks deep wounds – has been trotted out so much that it’s easy to forget how often there’s some truth behind the cliche. Sometimes it’s not an act. That person on stage is mining their anguish to make strangers laugh.

Why on earth would someone do that?

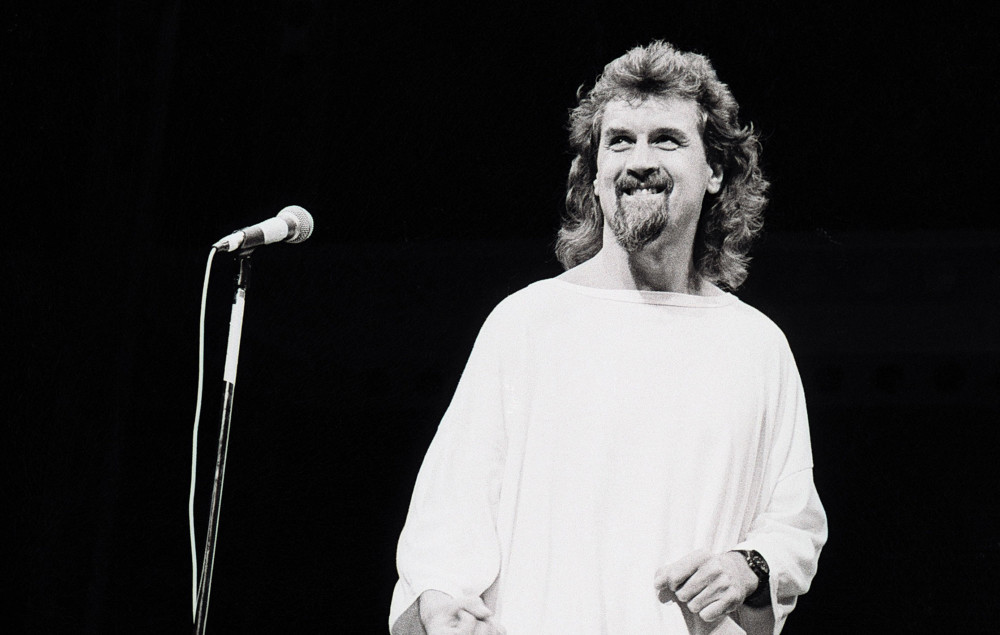

The comedian Billy Connolly spent a long time working out why he does it. For him, it’s therapy.

New Billy

Connolly’s traumatic early life is well known among his fans. He’s talked openly about the suffering he endured in childhood, even doing so on TV with his own wife, comedian-turned-psychotherapist Pamela Stephenson. And yet, Billy has little patience for the ‘comedian as sad clown’ cliche. He has every right to be sad, but watching him in interviews and behind-the-scenes segments, he comes across as a genuinely jolly and exuberant – some might say windswept and interesting – kind of guy. Make no mistake, he carries trauma with him but he’s found ways to deal with it. One of them is channelling his traumatic experiences and turning them into stand-up routines.

In 1992, Connolly was interviewed for the ITV arts programme The South Bank Show. This was the era of ‘New Billy’, symbolised by the recent removal of the scraggly goatee that had hidden the dimple in his chin since the 1960s. Interviewer Melvyn Bragg pointed out the change:

BRAGG:

The beard’s gone, the drinking’s gone, the smoking’s gone, the meat’s gone…CONNOLLY:

… the talent’s gone, the comedy’s gone.

Among the changes, Bragg pointed out how Billy had begun opening up on stage more about his traumatic childhood. Connolly was no stranger to taboos and controversial topics. His past stand-up material had covered sex, masturbation, religion, pubic hair, bodily functions and much more besides. But Bragg noticed he’d recently begun laying into the two ‘mad aunties’ who’d not only raised Connolly but had also – along with his father – left him with deep psychological scars.

Connolly agreed, he had been putting the boot in like never before. The time had come to purge. The people who’d raised (and abused) him were now gone – his father had died in 1988. After decades of dependency on alcohol, Billy had become sober. He’d regained his health, and not just physically. Self-medicating with booze had been replaced by therapy.

That therapy included talking to an audience of thousands and sharing painful stories. It was, for him, a cathartic release. In an example of the strange power of stand-up, his audiences responded by roaring with laughter.

Neglect

Connolly’s history of trauma goes back so far that he’s even mined his own conception for material. In one routine, he self-mockingly tells his audience he’s ‘damaged’, a ‘war baby’ conceived during an air raid. It’s certainly true that he was born in 1942. The Second World War was raging and his home town of Glasgow was bombed heavily, as if life wasn’t hard enough already.

His working class parents were young, his mother not even twenty, and they lived in a crowded tenement building. The flat had two rooms, no hot water, and a stinking communal toilet that served the family and the neighbours. Soon enough, Billy’s father was conscripted and shipped off to fight overseas, leaving his mother alone to take care of Billy and his older sister Florence.

The situation proved too much for his mother, who, Billy later remarked, was famed in the family for being ‘so volatile, she could start a fire in an empty room.’ She eventually walked out on her children when Billy was just four and they didn’t meet again until after Connolly became famous, something he joked about on stage years later:

She sold her story – or maybe she didn’t – but the Sunday Mail did a story on her, on Mother’s Day. Nice fucking touch, lads. [applause] She said I abandoned her. I thought, ‘who’s abandoning who here?’ [laughter] Four years of age, I remember the day she left. ‘Fuck off outta here!’ I said. [laughter] ‘Don’t show your face round here again.’

I’ve annotated quotes from Billy’s performances showing audience reactions to emphasise that he really was getting comedy out of his harrowing experiences.

There’s worse to come.

Abuse

With their father still away, Billy and Florence ended up in a children’s home, but were soon taken in by his father’s sisters, Margaret and Mona. This happy turn of events didn’t remain happy for long. Now saddled with young children, the two women saw their independence vanish and prospects of marriage plummet. Pride for doing their familial duty quickly turned to resentment.

Any affection towards their niece and nephew, however austere, was replaced by neglect and spiteful cruelty. Billy endured physical abuse. Like many parents and authority figures of the time, his aunts didn’t hesitate to enforce discipline using violence. ‘Spare the rod, spoil the child,’ as the old saying went.

Eventually Connolly’s father was demobbed and returned to civilian life, moving into the cramped tenement with his sisters and young children. Disappointingly for little Billy, Connolly Senior was just as ready to dish out a beating too.

Incredibly Connolly managed to turn even this into a comedic routine, focusing on the difference in how men and women hit children.

Men will tell you not to do a thing, then lose patience and go for you and it’s like being hit by a building [light laughter]. Your father would kick, punch, bite, elbow and gouge your eye all at once. [light laughter] You can tell it was coming when sentences started to fragment. ‘Get down off that wall, I won’t tell you again! … What did I tell you? … Get do– [growing laughter] … For Christ– If I have to– Aww for, if I– Come here!’ [mimes being punched and slapped in rapid succession and left in a daze] ‘What the fuck was that?’ [laughter] It was like being run over by a herd of cattle. [laughter]

But women hit you in the rhythm of the argument. Usually there’s two real haymakers to start. [mimes being slapped in time with each word] ‘Don’t … you … ever-let-me-catch-you-doing-that-again.’ [laughter, applause]

But he’s able to go even further.

In the snippet above, Connolly describes the abuse in a somewhat abstract way. In a different performance, he describes in visceral detail the pain and shock at being beaten as a child, and he’s very much the central character.

Uttered in a support group, these same words might provoke gasps of sympathy. But this is stand-up, and in stand-up context is everything. By this point in the performance, Connolly has already spent time forging a bond with his audience. His natural delivery makes the performance seem like a conservation, albeit one-way. His demeanour is upbeat and enthusiastic, signalling his willingness for you to laugh. Everything he’s done so far has relaxed the audience to the point that they can laugh at a story of childhood violence. Crucially, he is the victim. This is his experience, he owns it and is putting it before the audience, finding things in common, generating empathy, and discovering the funny side of it. It’s this skit in particular that once made me pause for thought, suddenly aware I was howling with laughter at the story of a child being beaten.

Home life kept him, in his own words, ‘a miserable wretch’ throughout his childhood. School wasn’t much better, a place where he discovered even more people willing to hit and humiliate him. He’s wrung laughter out of hardy P.E. teachers who berated him as a ‘big jessie’ for being crap at football. He’s made us cackle at his school trips to Aberdeen where he was forced to swim in the freezing North Sea, while a few miles out tannoy systems on oil rigs yelled out to their engineers: ‘All personnel must wear survival suits at all times. You wouldn’t last five minutes if you fell into the North Sea!’ He’s tickled our ribs recounting the cruel nuns at his Catholic school who smacked him for his ignorance (‘Whack! Billy Connolly, how come you don’t know the answer?’ ‘I don’t know anything, I’m only four, for fuck’s sake!’).

I could go on, but instead I’ll jump back to 1992 and that interview with Bragg because the idea of being a four-year old is pertinent.

I’m Only Four, For Fuck’s Sake!

Connolly reveals in the interview that he’s a recent convert to John Bradshaw’s theory of the inner child:

He [Bradshaw] reckons that, if this trauma happened to you when you were five or six, then emotionally that part of you remains five or six, and what you have to do is to carry that five or six year old around with you and try and emotionally help that other part of you […] and it can actually talk to you if you do it right, you can ask it things […] It has helped me immensely, so I find that by talking about it I have a great time and it rids me of all this nonsense that I was carrying around.

Since that interview, Connolly continued talking about painful things on stage, revealing to roomfuls of strangers uncomfortable experiences and intimate thoughts that the rest of us would hesitate to tell our closest loved ones. He’s joked about – among other things – his embarrassing attempts at losing his virginity, his father dying of a stroke, being naked in Trafalgar Square in broad daylight (‘in my defence, it was fucking freezing’), his colonoscopy, and the symptoms of his Parkinson’s disease. In each case, his audiences responded with roars of laughter.

In 2009, he sat down with his wife Pamela for an episode of Shrink Rap, an interview-stroke-therapy session. The inner child theory was brought up shortly after they’d discussed Billy’s recent and profound experience at an Inuit ritual in a sweat lodge.

PAMELA: You once told your biographer you thought you were four years old. How hold are you now?

BILLY: [thinks] Oh my God.

PAMELA: What number just came into your mind?

BILLY: Six.

PAMELA: You grew two years in that sweat lodge.

BILLY: [laughs] Four and a half came to mind as well.

Billy may have retired from stand-up, but his career stands as a testament to the ability of stand-up to explore and find the funny side of practically anything, even the tragic.

Next time, I’ll talk about another comedian whose childhood experiences were formative in his ability to make people laugh.

Leave a Reply