In the previous article, we learned how Rodney Dangerfield – still at this point known by the stage name Jack Roy – had abandoned his failed stand-up career only to be enticed back to the stage years later at the age of forty.

Breakthrough

When Rodney returned to the stage, there was a lot against him. He was clearly older than most of his fellow comedians, and the stench of failure from his earlier Jack Roy days still clung to him, making it hard to secure bookings. This forced him to venture out of New York to find clubs willing to give him a shot. He found some venues, but all those travel costs and hotel stays outweighed his earnings. In chasing his dream, he was losing money fast.

But while he faced many challenges, he also had some things going for him, perhaps more than he realised.

Comedians basically have to fail at life before you even know that you’re funny.

– Jeffrey Ross

For one thing, the stigma of the name was easily fixed. One night before going on stage, he asked the club owner to announce him with a name other than Jack Roy. Just like that, the owner came up with Rodney Dangerfield1. From that day on, nobody heard the name Jack Roy again.

But more importantly, 40-year old Rodney was more mature and experienced. His timing was better. While still basically dissatisfied with life, the raw anger of his youth had subsided somewhat. And, thanks to all those evenings spent writing jokes, he had a wealth of new material from day one. Those jokes reflected his perception of himself at the time he’d written them, namely as a downtrodden everyman for whom nothing goes right.

Critically, this gave him something that he’d lacked before: a distinct stage persona that audiences could truly connect with. The lack of his former on-stage belligerence left him a mellower character, one that people felt more comfortable laughing at, but one who nonetheless appeared near the end of tether, forever fidgeting and pulling at his tie. Yes, he was pissed off, but, like so many of us, he was resigned to his crummy lot in life. His gags now invariably featured himself as the victim, inviting the audience to cackle at his rotten luck. Like that little boy at the dinner table who’d insisted he hadn’t had any fish, he was making himself the butt of the joke.

I could tell my parents hated me. My bath toys were a toaster and a radio.

I went to see my doctor. I told him, “Doctor, every morning when I get up and look in the mirror I feel like throwing up. What’s wrong with me?” He said, “I don’t know, but your eyesight is perfect.”

On Halloween, the parents send their kids out looking like me.

My wife is always trying to get rid of me. The other day she told me to put the garbage out. I said to her I already did. She told me to go and keep an eye on it.

It wasn’t the only thing that chimed with people. The cherry on the cake of Rodney’s reinvention was the thing he’s probably most remembered for: that legendary catchphrase.

I don’t get no respect, no respect at all!

Comedian Jack Benny once remarked on the power of that catchphrase, claiming it hits a nerve and expresses a universal feeling among people that they don’t get the respect they deserve.

As Rodney developed this persona, audiences began lapping it up. Word spread. Soon, those New York club owners that’d shunned Rodney were welcoming him back. He spent several years on the circuit again, building up his fame and honing his new act, until he reached the limits of success offered by the local club scene. By 1967, he felt ready for the next level: national exposure.

He eventually got it by appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, a top-rated variety show on American station CBS that reached an audience of millions. Incredibly, he was still working his day job as a salesman. Things were good, but not that good, and he had a family to support. However, his five-minute slot on Ed Sullivan brought him to the attention of people all across the nation.

He didn’t remain a salesman much longer.

Growing Old, Staying Young

After Rodney’s appearance on television, offers began flooding in. He continued appearing on Ed Sullivan, but also became a regular performer on other massive shows like The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and The Dean Martin Show. He was invited to play in Las Vegas, where he earned thousands of dollars per act. Now approaching fifty years old, he’d finally achieved huge success.

In the process, he’d struck a blow against the ageism that afflicted stand-up comedy. He proved it was never too late in the youth-worshipping industry. In fact, Rodney would go on to defy the conventional wisdom regarding age in several other industries. The first instance of this was prompted by, of all things, his wife’s failing health.

Despite having divorced in 1961, Rodney and Joyce had remarried in 1963. By the time of Rodney’s breakthrough, Joyce had developed crippling arthritis, leaving her struggling to look after their young children. Rodney was left in a dilemma: Joyce’s illness meant he needed to stay in New York to help with the family, a choice that was incompatible with working heavily in Vegas.

He came up with a solution. Deciding he didn’t want to be an absentee father (like his own), he turned his back on the lucrative Vegas gigs and invested in opening a Manhattan-based comedy club. In 1969, such a move seemed an act of lunacy. Night clubs and cabarets were closing everywhere in face of stiff competition from television. But Rodney was blazing a trail. Although the club Dangerfield’s wasn’t the very first, it was among the earliest of a new type of club focusing solely on stand-up. Within a year, it was profitable. Soon after, comedy clubs just like it would sprout up across the USA and many other countries, like The Laugh Factory, Yuk Yuk’s and The Comedy Store. The fifty-year old Rodney had thus succeeded as an entrepreneur, another career where youth is traditionally all but an entry requirement.

And he wasn’t finished yet.

Throughout the 1970s, Rodney was content to remain in New York, being there for his children during the day and performing at his club in the evening. Occasionally he’d fly out to Los Angeles to do a television gig like an appearance on Johnny Carson – where he could keep up his profile, earn some bread, and plug Dangerfield’s – but on the whole he remained a family man.

By the end of the decade, his children were approaching adulthood. Their independence coincided with the arrival of an interesting offer from a film studio. Orion Pictures was making a movie with some of those young upstarts from Saturday Night Live and wondered if Rodney would like to appear in it. The film’s name was Caddyshack.

Rodney role was Al Czervik, the boorish nouveau riche property developer who turns up at the fusty Bushwood Golf Club wanting to buy the place and turn it into condominiums. He arguably stole the film, not bad going when you consider this was his first big role and he was sharing the screen with fresh-faced comedy stars like Chevy Chase and Bill Murray. Weirdly, although he was now pushing sixty, Rodney was the cast member who most embodied the rambunctious energy of carefree youth as he strutted through the film flinging out one-liners, giving the finger to crusty fuddy duddies, and declaring in the last line of film, ‘Hey everybody, we’re all gonna get laid!’

He went on have the lead role in several more comedies, including Back to School. In this film, he starred as a successful businessman who joins his son in enrolling at university and embraces college life, living it up like a man one-third his age. It ended up the sixth highest grossing film of 1986, earning more money than classics like Aliens and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Once again, Rodney had defied conventional showbiz wisdom, this time by becoming a big comedy movie star despite closing in on retirement age.

The Last Laugh

It’s into your soul from a youth: if you feel nothing goes right or you weren’t treated right, it stays with you to the end.

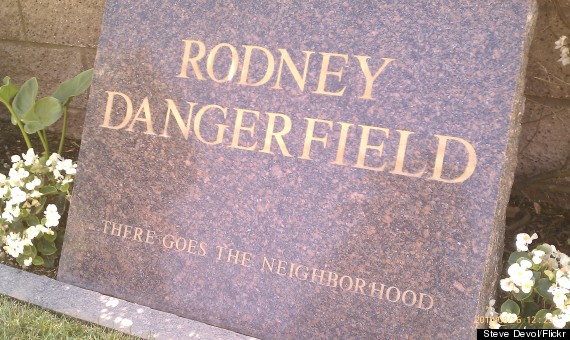

Rodney never did retire. He couldn’t really, not when the pain of his youth continued to haunt him and the only real relief came from comedy. He continued to act, perform at his club and show up on chat shows, getting his fix right up to the end, which came in 2004. True to form, he was still quipping right before his final heart surgery. When asked how long he’d be recovering, he replied, ‘If all goes well about a week. If not, about an hour and a half.’

He had many professional achievements, but the one I’d most like to highlight is how he bucked the trend and proved to the world that you’re never too old. Comedy – as is surely true of many other walks of life too – doesn’t have to be just a young man’s game.

- The origin of the name is not clear, but it may have been taken from a character played by Jack Benny on the NBC radio show The Jack Benny Program. ↩︎

Leave a Reply